Scientific

ScientificPolice have destroyed more than 100 dangerous dogs a month on average since bullies were banned almost a year ago, the BBC has learned.

Forces in England and Wales say the costs of keeping thousands of seized dogs, often for several months, had risen sixfold to £25 million a year, and many facilities had reached maximum capacity.

But in many areas dog attacks show no sign of abating. Of the 25 police forces that responded to the BBC’s Freedom of Information Act requests, 22 said they were on track to see more incidents reported this year.

Lisa Willis, who was attacked by a bully months into the ban, said the attack looked like a “horror movie” and the law was “useless”.

She said owners of dogs like the one that attacked her arm should be banned from buying more animals. However, in her case, the owner replaced his dog “within a matter of weeks.”

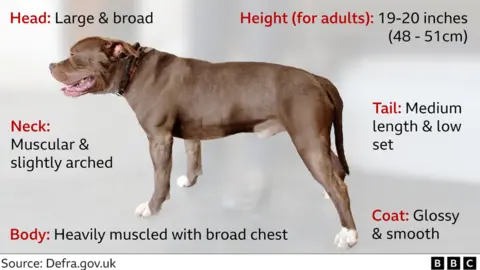

New laws restricting the breeding and sale of XL bullies came into effect on December 31 last year after a series of high-profile attacks, some fatal. In February, it became illegal to own a dog of this type, unless it is registered before the deadline.

There are now five types of dogs banned in Britain: the XL Bully, Pit Bull Terrier, Japanese Tosa, Doga Argentino and Fila Brasiliero. Dogs registered before the ban must be neutered, muzzled in public places and kept in safe conditions.

When the law was introduced, the UK government suggested there were around 10,000 XL bully dogs in England and Wales, but this was a vast underestimate – there are now more than 57,000 bully dogs registered with the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra).

Freedom of Information Act responses from 19 police forces in England and Wales show that in the first eight months of 2024:

- 1,991 suspected banned dogs were seized, up from 283 in all of 2023

- 818 dogs were destroyed, more than double what was destroyed in 2023

With some seized dogs remaining in police kennels for several months until their breed or type is confirmed, more than half of forces who provided responses about their kennels said they were full or close to capacity.

Once a court order is issued or dogs are released by their owners, they are euthanized by a veterinarian.

Chief Constable Mark Hoboro, leader of the National Police Chief’s Council on Dangerous Dogs, said the change in the law had put significant pressure on police forces and added an “incredible” amount of extra costs they had to absorb.

Kennel costs and veterinary bills have risen from £4 million to £25 million, but this does not include the additional costs of training staff, purchasing additional vehicles and equipment, short-term kennel hire, and the wider operational costs of monitoring high-risk dogs. He said: More than ever.

He said the NPCC is making a “strong request” for more government funds to meet the requirements of the Bully XL ban.

Chiefs of the 43 police forces in England and Wales also want to change the law to give officers alternative ways to deal with people caught in possession of dangerous dogs.

Part of what makes monitoring bans difficult is that knowing whether a dog is too bully can require specialized training and sometimes outside expertise, which means keeping dogs in kennels for long periods.

The government has published guidelines to help identify XL bullies, which are defined as a “type” of dog because they are not a breed recognized by the Kennel Club. They are described as large dogs “with a muscular body and stocky head, suggesting great strength and endurance.” [their] measuring”.

Expert assessors have told us that up to a third of dogs registered with Defra may not be XL bullies, but there is still no guidance on how to remove them from the register.

Police chiefs want to see changes that would allow them to warn responsible owners who may have unwittingly bought an XL bully, while still having strong powers to crack down on illegal breeders and persistent offenders.

Defra said the XL bully ban was “an important measure to protect public safety” and it would continue to work with police, local authorities and animal welfare groups to prevent dog attacks “using the full force of the law where needed”.

In Lisa’s case, she was walking her dog, Doc, in June, when a French bulldog attacked him. Moments later, a bully dog emerged from the garden, crossed the road and attacked Lisa.

“I just thought he was going to kill me,” she said. “It was so strong, it was hanging on my arm, and no matter what, I couldn’t get it off.”

People nearby heard her screaming and helped get the dog away from her, but she said her arm was “torn off.” She was afraid she would bleed to death and asked rescuers to call her husband “so I could say goodbye to him.”

Lisa, who She contacted us about her story through Your Voice, Your BBC Newswas taken to the hospital. Police confiscated and destroyed the animal that attacked her on the same day, which is normal procedure when a dog is involved in a serious accident.

She is being treated for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and says she feels “powerless” to prevent something like this from happening again.

“I need to make sure that these people have consequences for their actions because if they continue, someone else will be killed, someone else will be attacked,” she said.

Additional reporting by Jonathan Fagg and Emily Doty